THE INHERITANCE OF NICHE

Early on in the Inheritance of Loss, Kiran Desai has the cook lighting a small fire to boil water for tea. She has him so scared of those plump scorpions in the wet firewood, that he uses a stick to turn the damp wood pieces on the pile. For an odd moment, this setting with the kettle of boiling water hissing in the dark, dank kitchen of a dilapidated, dirty and grey home in Kalimpong, seemed strangely reminiscent of another world; a world created by another Desai in another day and age.

That was more than two decades ago. The protagonist sat drinking chai at a teashop on a wooden bench. The book was In Custody and the writer was none other than Kiran's mother, Anita Desai. The protagonist, as you may have well guessed by now was Deven, the lecturer of a college in Mirpore, on his way to interview the great Urdu poet Nur Shahjahanabadi in Delhi's Chandni Chowk. Tired after a bus journey, he had stopped for a cup of tea on the roadside. The plot highlighted a world where there was talent, fame, sensitivity on the one hand, while on the other was genteel poverty. Perched in the wedge between the two, one could distinctly recall the same dark, dank slice of life that the Junior Desai now portrays in her new book: the world of doubt and shadow, of identity and inequality and of diffidence and unfulfillment, that almost always accompanies the sense of loss or unbelonging.

When I first "discovered" Anita Desai's works it felt like seeing India through a new lens. The steady diet of Jeeves and Reginalds and the antics of the three men in a boat, which I had hitherto been raised on, was never my world. Make no mistake though- I am a great fan of P.G. Wodehouse, my love for H.H. Munro (Saki) 's brand of subtle humor still endures, and I can't remember a time when I didn't laugh my head off at Jerome K. Jerome's comic prose. However, it was also a world I could scarcely identify with. It needed huge doses of imagination to picture their royal highnesses, those dukes and duchesses in full regalia who sat in lovely manicured lawns where the afternoon teas were served to the accompaniment of buttered scones by gloved butlers. When came the time for their lordships to depart, they would do so in their buggies after having successfully negotiated the carriage steps with the liveried coachman's help.

This world encompassed us so totally that even after 35 years of independence most Indian-English fiction still reeked of the Raj. We were still feasting on Kipling and Forster and when we wanted a respite, out came the Jane Austens and Bronte sisters. For the highly cerebrals, there were always the family of the Stuart Mills. Something had to be said for the fact that in the creative writing courses we had in school, almost everyone wrote about this Anglicized world. I remember how our annual school magazine short stories were more about Counts and Countesses than schoolteachers, clerks or regular people. And how the dum aloo subzi we young girls ate at home, miraculously transformed into baked potato Vichyssoise with red caviar once it reached the fictional dinner tables of our characters.

True, there was R.K.Narayan, but his Malgudi,though geographically in India's perimeter, lacked its earthiness. The characters were Indian, wore Indian clothes and ate Indian food, but there was a strong Anglicized upper class ethos overall. Then there was the other founding father of the Indian English novel. But Mulk Raj Anand's India of Bhangis like Bakha (The Untouchable), touching and poignant though their tales were, needed a different sort of imagination to figure out. That left Nehru and Gandhi and the whole freedom fighter clan of erudite writers, who we did read now and then. But in the winter of 1984, the worlds of the Lahore Congress and Quit India Movement and the Round Table talks seemed equally alien.

In the meantime, unbeknownst to our group of friends, Salman Rushdie had arrived with his Midnight's Children in 1981. Thanks to the Booker, we did hear his name, though it would be many years before I could lay my hands on his first book. I am glad it happened when it did and not earlier, because Rushdie's was hardly the sort of fiction for young readers to cut their teeth in, much less comprehend.

But Anita Desai's was not. It was a treat to read of the Devens and Murads and the Nur Sahabs and of their sadness, tongue tiedness, pushiness, meanness; to see them scoop subzi with a roti and eat radishes with relish. Why, even their dals, like ours, came loaded with small stones (this is the mid-eighties when dals came from ration shops and weren't perched on fancy supermarket shelves). It was quite reassuring to see their roads littered with cows and cowdung (with the former around can the latter be far behind) where one could easily be hit by a rickshaw if one wasn't careful. Dust and grime were omnipresent, as were blaring loudspeakers. Road side stalls sold oily food in dirty dishes wiped dry with equally dirty rags. And when the characters were distraught, the cause was usually more genuine than not wearing matching pearls to the Viceroy's ball or missing the tiger's forehead by a tiny inch in last shikar. In short, Desai Senior's rare eye for detail and fine minutiae captured what was so uncannily and quintessentially Indian that I yelped with joy. It seemed that the soul of India lay bare before us. A soul where beggars, clerks, shopkeepers, teachers, poets, learned men (may be even men of royalty) all jostled for their place. And each came away with their own sense of unbelonging in the context of the whole.

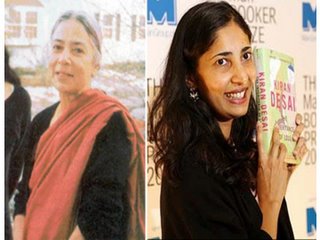

It is precisely this feeling that resonates through the Kiran Desai's Booker winner work. Her characters, too, live in various degrees of unbelonging. If the Anglophiles of Kalimpong with their Swiss cheese and broccoli, and Mark and Spencer's underwear don't belong, neither do the Nepali insurgents who live and work in poverty. Neither does Sai, the young protagonist, who by virtue of being raised amongst the elderly and being home schooled, does not quite belong to the world of the young. In distant New York too, where the cook's son, Biju, works in restaurants and saves money to send back home, there is the same sense of not quite belonging to the new world order set by immigration laws, work permit papers and quick profits.

The era of Unbelonging is no longer caged in any time or shore. It is now a zeitgeist. And Kiran Desai has none other than her mother to thank for that.

Early on in the Inheritance of Loss, Kiran Desai has the cook lighting a small fire to boil water for tea. She has him so scared of those plump scorpions in the wet firewood, that he uses a stick to turn the damp wood pieces on the pile. For an odd moment, this setting with the kettle of boiling water hissing in the dark, dank kitchen of a dilapidated, dirty and grey home in Kalimpong, seemed strangely reminiscent of another world; a world created by another Desai in another day and age.

That was more than two decades ago. The protagonist sat drinking chai at a teashop on a wooden bench. The book was In Custody and the writer was none other than Kiran's mother, Anita Desai. The protagonist, as you may have well guessed by now was Deven, the lecturer of a college in Mirpore, on his way to interview the great Urdu poet Nur Shahjahanabadi in Delhi's Chandni Chowk. Tired after a bus journey, he had stopped for a cup of tea on the roadside. The plot highlighted a world where there was talent, fame, sensitivity on the one hand, while on the other was genteel poverty. Perched in the wedge between the two, one could distinctly recall the same dark, dank slice of life that the Junior Desai now portrays in her new book: the world of doubt and shadow, of identity and inequality and of diffidence and unfulfillment, that almost always accompanies the sense of loss or unbelonging.

When I first "discovered" Anita Desai's works it felt like seeing India through a new lens. The steady diet of Jeeves and Reginalds and the antics of the three men in a boat, which I had hitherto been raised on, was never my world. Make no mistake though- I am a great fan of P.G. Wodehouse, my love for H.H. Munro (Saki) 's brand of subtle humor still endures, and I can't remember a time when I didn't laugh my head off at Jerome K. Jerome's comic prose. However, it was also a world I could scarcely identify with. It needed huge doses of imagination to picture their royal highnesses, those dukes and duchesses in full regalia who sat in lovely manicured lawns where the afternoon teas were served to the accompaniment of buttered scones by gloved butlers. When came the time for their lordships to depart, they would do so in their buggies after having successfully negotiated the carriage steps with the liveried coachman's help.

This world encompassed us so totally that even after 35 years of independence most Indian-English fiction still reeked of the Raj. We were still feasting on Kipling and Forster and when we wanted a respite, out came the Jane Austens and Bronte sisters. For the highly cerebrals, there were always the family of the Stuart Mills. Something had to be said for the fact that in the creative writing courses we had in school, almost everyone wrote about this Anglicized world. I remember how our annual school magazine short stories were more about Counts and Countesses than schoolteachers, clerks or regular people. And how the dum aloo subzi we young girls ate at home, miraculously transformed into baked potato Vichyssoise with red caviar once it reached the fictional dinner tables of our characters.

True, there was R.K.Narayan, but his Malgudi,though geographically in India's perimeter, lacked its earthiness. The characters were Indian, wore Indian clothes and ate Indian food, but there was a strong Anglicized upper class ethos overall. Then there was the other founding father of the Indian English novel. But Mulk Raj Anand's India of Bhangis like Bakha (The Untouchable), touching and poignant though their tales were, needed a different sort of imagination to figure out. That left Nehru and Gandhi and the whole freedom fighter clan of erudite writers, who we did read now and then. But in the winter of 1984, the worlds of the Lahore Congress and Quit India Movement and the Round Table talks seemed equally alien.

In the meantime, unbeknownst to our group of friends, Salman Rushdie had arrived with his Midnight's Children in 1981. Thanks to the Booker, we did hear his name, though it would be many years before I could lay my hands on his first book. I am glad it happened when it did and not earlier, because Rushdie's was hardly the sort of fiction for young readers to cut their teeth in, much less comprehend.

But Anita Desai's was not. It was a treat to read of the Devens and Murads and the Nur Sahabs and of their sadness, tongue tiedness, pushiness, meanness; to see them scoop subzi with a roti and eat radishes with relish. Why, even their dals, like ours, came loaded with small stones (this is the mid-eighties when dals came from ration shops and weren't perched on fancy supermarket shelves). It was quite reassuring to see their roads littered with cows and cowdung (with the former around can the latter be far behind) where one could easily be hit by a rickshaw if one wasn't careful. Dust and grime were omnipresent, as were blaring loudspeakers. Road side stalls sold oily food in dirty dishes wiped dry with equally dirty rags. And when the characters were distraught, the cause was usually more genuine than not wearing matching pearls to the Viceroy's ball or missing the tiger's forehead by a tiny inch in last shikar. In short, Desai Senior's rare eye for detail and fine minutiae captured what was so uncannily and quintessentially Indian that I yelped with joy. It seemed that the soul of India lay bare before us. A soul where beggars, clerks, shopkeepers, teachers, poets, learned men (may be even men of royalty) all jostled for their place. And each came away with their own sense of unbelonging in the context of the whole.

It is precisely this feeling that resonates through the Kiran Desai's Booker winner work. Her characters, too, live in various degrees of unbelonging. If the Anglophiles of Kalimpong with their Swiss cheese and broccoli, and Mark and Spencer's underwear don't belong, neither do the Nepali insurgents who live and work in poverty. Neither does Sai, the young protagonist, who by virtue of being raised amongst the elderly and being home schooled, does not quite belong to the world of the young. In distant New York too, where the cook's son, Biju, works in restaurants and saves money to send back home, there is the same sense of not quite belonging to the new world order set by immigration laws, work permit papers and quick profits.

The era of Unbelonging is no longer caged in any time or shore. It is now a zeitgeist. And Kiran Desai has none other than her mother to thank for that.

13 Comments:

very good Shampa, now I must read them all.

Neel

thanks

Shampa

I read this piece of writing completely about the resemblance of most up-to-date

and previous technologies, it's awesome article.

my weblog ... applestemcellserum.net

Fantastic goods from you, man. I've understand your stuff previous to and you're just extremely wonderful.

I actually like what you've acquired here, really like what you are saying and the way in which you say it. You make it entertaining and you still take care of to keep it smart. I cant wait to read far more from you. This is actually a wonderful site.

Also visit my site ... Pur Essence Anti Wrinkle

Everything is very open with a precise clarification of the

issues. It was really informative. Your website is useful.

Thank you for sharing!

Here is my page - uy Le derme luxe

Thanks to my father who stated to me regarding this website, this website is actually amazing.

Look into my webpage ... Le parfait skin reviews

This article is in fact a fastidious one it assists new internet people, who

are wishing for blogging.

my web blog ... Online pay day loans

I do agree with all of the ideas you've presented for your post. They are really convincing and can certainly work. Still, the posts are very short for novices. May just you please lengthen them a little from subsequent time? Thanks for the post.

Feel free to visit my web site; Test Force Extreme

What's up, just wanted to mention, I enjoyed this post. It was funny. Keep on posting!

my webpage - Garcinia Cambogia Supplement

You should be a part of a contest for one of the finest sites online.

I am going to recommend this web site!

Here is my web blog ... Lift serum pro reviews

Please let me know if you're looking for a article author for your site. You have some really good posts and I feel I would be a good asset. If you ever want to take some of the load off, I'd really like to write

some material for your blog in exchange for

a link back to mine. Please shoot me an e-mail if interested.

Kudos!

Here is my webpage XtraSize

I am regular visitor, how are you everybody? This piece of writing posted at this site is genuinely pleasant.

Also visit my web page; Test Force Xtreme Review

Fantastic website. Lots of helpful information here.

I'm sending it to some pals ans also sharing in delicious. And obviously, thank you for your sweat!

Review my website Working Online

Post a Comment

<< Home